Latin for Gardeners

January’s Native Maryland Plant

Quercus palustris (Münchh.)

(KWER-kus pa-LUS-tris)

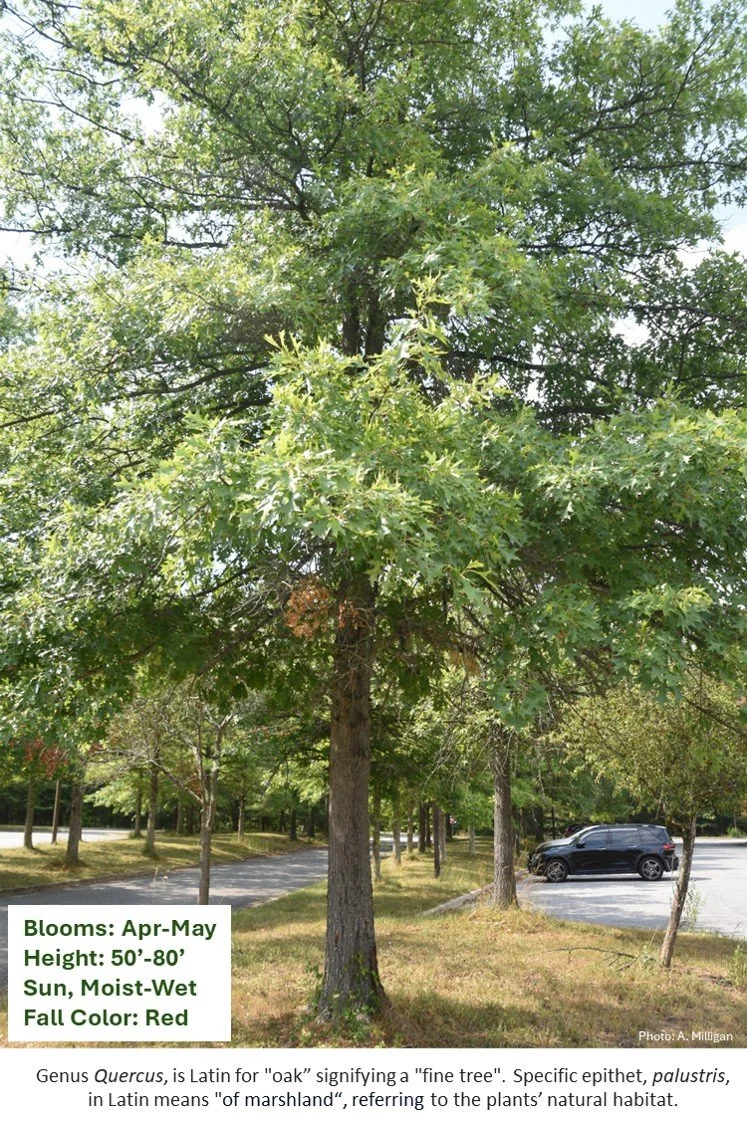

Quercus palustris are one of the very fine red oak trees that are commonly planted and easily recognized along roadways, in resident landscapes and even in parking lot islands – and for good reason. This plant is fast-growing, it tolerates urban stress, pollution and many soil conditions. Of course, being an oak it’s also a major contributor to the food web – its leaves are eaten by a vast number of insects (think very hungry caterpillar) while its acorns feed many other animals – including the very hungry squirrels in my yard.

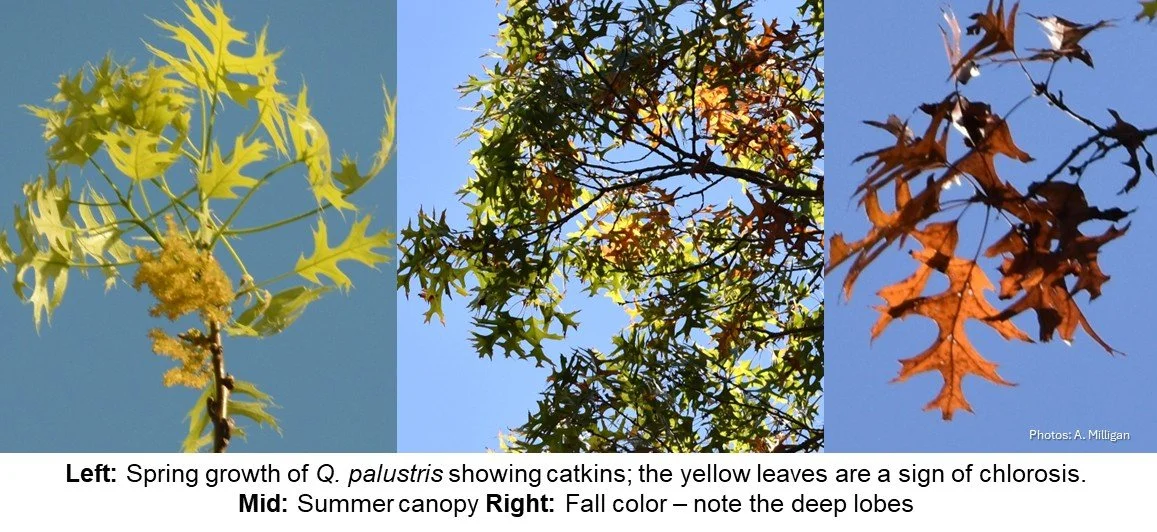

The only notable exception to the plants’ toughness is its intolerance of alkaline soil which reduces its ability to take up iron, causing iron chlorosis 1 . New growth will generally exhibit the most obvious symptoms, yellowing of the leaves, since without iron the plant can’t produce chlorophyll. The best way to avoid the condition, which can be fatal, is to not plant a Q. palustris in soil that tends towards alkaline (pH 6.5 or below is preferred). If chlorosis is observed and you can manage it, you can take advantage of another strength of this tree – it’s highly transplantable so it can withstand being moved to a more suitable acidic location.

Pin oaks can be seen at the Patuxent Research Refuge in Prince George’s county Maryland. It is the only National Wildlife Refuge in the country established to support wildlife research.

The refuge is a wonderful place to visit in the winter; there are many trails to explore and experience the wonders of the season. The Visitor Center is a destination itself, with many interesting exhibits. This month they’re featuring a photo exhibit by David Jonathan Cohen titled “In the Galápagos Islands”, a place where you’ll find unique plants and animals but no Quercus palustris.

1) Iron chlorosis is the result of a lack of iron in the new growth of a plant. Iron is not necessarily deficient in the soil—it may be there, but just in an unavailable form for absorption through the root system.

NOTE: Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa) is one of the oaks that is tolerant of highly alkaline soils and drought. It was featured in January 2025’s Latin for Gardeners’.

Alison Milligan – MG/MN 2013

Watershed Steward Class 7/Anne Arundel Tree Trooper

Chesapeake Bay Landscape Professional (CBLP)

alison@lifewithnativeplants.org